The work of Julius Thissen is focused on transgender visibility in contemporary art and media. In their research-based art practice, Thissen investigates the history and ethics in the representation of transgender people. Their work aims to counter stereotypes and binaries that often prevail in the portrayal of trans individuals. Thissen spent the last month in Riga as a FUTURES resident at ISSP. We met up to speak about their time at the residency, the artistic vision and the political significance behind their work.

You’ve spent the last month in Riga as a FUTURES resident artist at ISSP. Can tell me a bit about what you have been working on here at the residency?

I arrived with two focus points. One was to connect to the local trans and queer community and to have conversations with them. I met up with trans and queer people who also identify as activists and are trying to make changes or to create community and gathering moments. I was very happy to speak to them and hear more about their context and their visions, trans emancipation and trans rights. Out of respect, I won’t share the things that struck me or that I heard from them as these are rather sensitive subjects and I don’t think it would be right for me to speak about that after being here for a month. But I’m very grateful that they were so generous with their time to share their visions, ideas and experiences with me.

Next to that, I’m working on a big photo project. It has a lot of research in it and also connects to my conversations here. I recently shot photographic material for a new character for that project. I spent most of my time here editing and seeing how that connects to the bigger photo series that I’ve been working on.

Those things combined led to an artist talk in Riga. That was a really nice way for me to talk about trans visibility in a Latvian context and to have people in the room who weren’t familiar with trans people in general or trans visibility history from a Dutch perspective. The talk initiated amazing conversations and connections.

Your background is in performance so I wanted to ask what interests you in photography as a medium and how performance has informed the type of images that you’ve developed?

When I graduated [from art school], I made durational performances about Western toxic masculinity, which I would document in film and the film would be the end result. I spent four years making these films with my muse, also a man. In that work we would reenact toxic masculine stereotypes and look for our physical or our emotional limits. The performances were successful: there was an audience for them and they were doing well for me from a career perspective. At a certain moment I was feeling like the process was becoming a bit repetitive and I was also bumping into some technical limits with film as you can only manipulate it so far.

I have a background in photography from my study days. At the time, I was considering becoming a fashion photographer, but then after spending time in Paris in 2013 for an internship I discovered that for me, a feminist, the fashion industry doesn’t fit with my ideals. Plus, my art school really kind of frowned upon everything that had to do with aesthetics and fashion if it was shiny and polished. They didn’t want anything to do with it and didn’t believe it was art. Eventually I started performing and making these films, but slowly, four years after graduating I started moving back to photography. Now, ten years later, I really embrace my background in fashion photography. I use that aesthetic language and costume history as a way to lure people into my images. At first glance, my images might seem as shiny editorial looking photographs, but then once you are in, it turns out that it’s socially and politically loaded work. I use it as a tactic to say — come, look at the shiny aesthetic work, but then really start talking about feminist topics, trans rights and political power structures.

That’s why I moved to photography again. I also love how much you can manipulate a photo. I can take a picture and completely mutate the person who I’m portraying or do it to my own body. You can have a lot of control over a photographic image — it’s been a lot of fun trying to master that and make it my own.

Speaking about fashion — what do you think draws you to it? It is an industry that is very tied to capitalism and body image.

I studied in ArtEZ in Arnhem and the school has a fashion department. I really connected with the students from the fashion department because of their work ethic and because it was one of the only places in the school where people were thinking about identity. I was in the fine arts department and back in the day identity was really not a thing, it was not something that you would make work about. I was looking at the fashion students and how they were creating amazing visual storytelling moments: it was way more than the clothing you see in the fast fashion industry. There I also met my longtime collaborator Joris Suk, who runs the fashion house MAISON the FAUX together with Tessa de Boer. We grew up together artistically and have been working on each other’s projects since. We believe in the potential of fashion as a political tool to question identity and power relations.

Costume history tells a very interesting societal story. A bespoke suit can tell you a lot about how masculinity has developed in relation to politics. The suit is a piece of clothing, but it speaks about power and corporate identity. If you look at a corset, it tells a story about women’s rights, emancipation, and liberation. I’m interested in costume history as a way of navigating the times and seeing how have things changed. The shaping of identity also goes together with expressing oneself with what you wear. I think that there is a lot of potential in playing very thoughtfully with all of these coded materials and then making them your own. For instance, if I, as a trans masculine person, decide to put on a corset in this day and age — what does that mean?

During your talk in Riga, you spoke about your ongoing project Bones of Graphene, Skin of Kevlar, which departs from your ongoing work on transgender visibility in the current context of far right politics on the rise. The images are pretty abstract and almost poetic, can you speak a bit about that?

For the last ten years, I’ve been researching transgender visibility. The most important thing for me is not just creating visibility but moving towards representation: what does being visible mean and how do we create visibility that can also be safe, empowering and can demand social change? When we look at the history of trans visibility in traditional media in the Netherlands, from the 70s onwards, we were almost exclusively visible within a medical narrative. If you would see us on TV, we would often be talking about our transitions, our operations, our hormones. Often there were non-trans people asking the questions to a trans person in a television show that had no trans people in the team. This created a dehumanised narrative about trans people — we were never seen as individuals who have hobbies, careers, visions, are politically active.

That has a lot of consequences also when you look at art. In museum collections often there is no representation of trans people or when we see trans people in museum collections, they are often naked and are showing their signs of transition. This just did something to me as a young artist. And I think when I just graduated, I wasn’t mature and strong enough to really make work about it. I was also experiencing the negative effects of such a narrative in the art world: I would be asked very private questions, for instance, about my genitals in meetings with curators or directors.

A few years ago I started feeling ready to start creating a form of representation that felt right for me and in which trans people have the right to choose to be visible. When their body is visible it’s either very abstracted, which keeps it safe, or very protected by the use of specific fashion items or workwear, or more recently by the use of prosthetics to alienate and mutate the trans body. For me it feels really off-key to see photography of trans people being soft and embracing each other with their eyes closed, leaning on someone else’s shoulder in this day and age. It is beautiful and important work, but there are people getting killed out there. What does that mean when we think about visibility? I think it’s important to make work that mirrors and reflects on these times, and attempts to incorporate these wars, this violence and danger without losing hope, strength and resilience to move forward. I always try to look for a very fine line in that and that’s a tension within which to operate in.

In your presentation in Riga, you made a distinction between non-committal trans visibility with a lack of agency and trans led visibility with agency.

In my talk, I spoke about of the negative narratives and the dynamics that have been going on and their consequences. But it’s also important to talk about the positive examples. What I mean with non-committal visibility is when trans people are gazed at. For instance, in the Netherlands we had this TV show Hij is een Zij, translated as He is a She, about trans people and their transition journeys. This was often presented by cisgender men who interviewed trans people about their physical and transitional needs and journeys. The show was made for cisgender people as a trans spectacle to watch with a bucket of popcorn or a bag of chips without realising that we are a very precarious and marginalised part of society. That for me is the perfect example of a non-committal form of visibility — it’s really made to entertain or to answer to a specific curiosity. Of course, for some trans people seeing that television show was also beneficial and it made them realise, hey, I can connect to this story, but after that there were no other sources to make that picture whole.

As a trans person, a potential transition is only one part of your life, there’s a whole spectrum of things that makes you human and that’s a perspective we haven’t been seeing. It’s visibility that has been created without agency. Agency means that there should be trans people at the table as directors and screenwriters thinking up specific programs. Positive examples are, for instance, television shows like Euphoria, POSE, Disclosure. In the case of Euphoria, there is a trans person in a lead role and it is empowering: Hunter Schafer played the role of Jules, who is kind of a wise-owl and is helping the main protagonist move through life. Of course, in this series we also see her struggles with being trans and specifically with being a trans woman — she is objectified and fetishised. But throughout the whole thing we see that the main character, who is a cis girl, turn to Jules for advice and support. For me, it was one of the first times seeing a trans person on TV as this powerful rock or pillar for somebody non-trans to hold onto. Hunter Schafer has since become a big star, has been very visible and has covered big fashion magazines.

Indeed. And I think the shadow side of that is that we need to realise that Hunter Schafer has a lot of privilege going for her. She is what society deems attractive, she is white, able-bodied and lean — that is also a different side of visibility that we should also be aware of. Who gets to be visible often follows the normative society standards that are already there. In my photo series, you often see characters that try to break with those codes saying that a trans person has to be extremely successful, sexy or desirable by societal standards to be able to be seen and to be accepted. I try to make work where that pattern gets broken, because I think that we should make space for the mediocre trans person to be able to live. Not all of us are Nikkie de Jager, people who are extremely talented at a specific trade or are successful from a capitalistic sense. Those are all questions and layers that I think we have to be aware of when we speak about visibility and representation.

What do you think that visual arts can do to advance the politics of solidarity and Inclusivity?

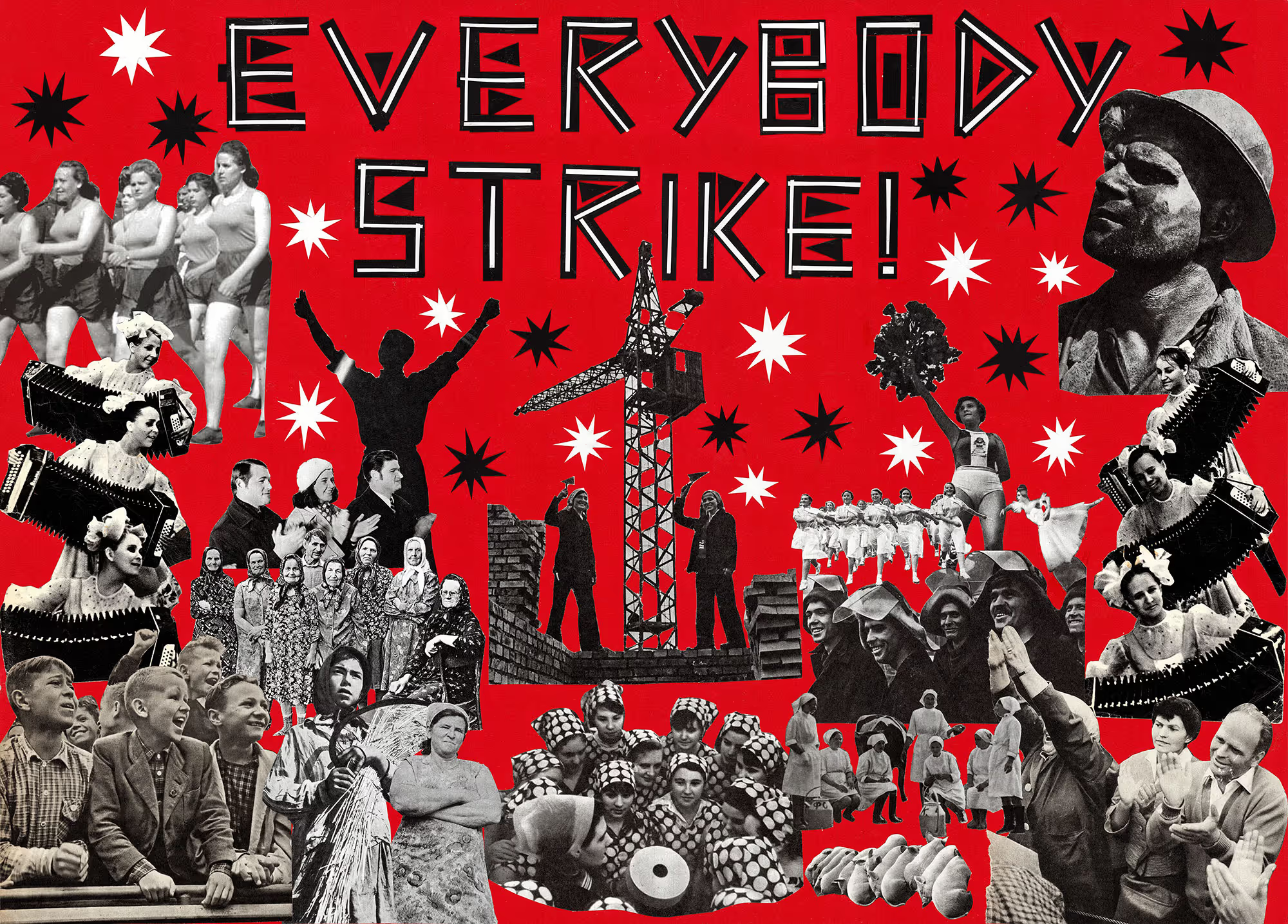

I think that art is a way to protest, to express visions, ideas or needs that are deemed to be unacceptable, too radical or unimaginable in the broader society. I think it’s really where things can be born without them having to be something yet and I think it can really also influence public thinking. For me, all career things aside, I make images to start a conversation. I hope that it can give the opportunity for somebody who wasn’t aware of all of these dynamics to maybe learn something about that, or for another trans person who has felt stuck in expressing their anger or their sadness to see an image of mine and then think that, oh, maybe I can talk to him about this. Anger and sadness are two of the things that trans people are not really allowed to express so I think it’s a way to open doors to conversation and imagination. That’s what I really wish for us — after being pacified in history for so long, after being oppressed for so long, I think art can be a beautiful and safe way to break free from that. Hopefully, politically things can follow. It wouldn’t be the first time in history that art creates a moment like that.

Images © Julius Thissen

.avif)

.avif)

%2520Unseen-campaign-2024-square-forweb.jpeg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

%252C%25202015.jpeg)