since 2017

European

photography

platform

Welcome to the European photography platform here you can explore a network of photographers, members of the platform and read more about us.

Artist Projects

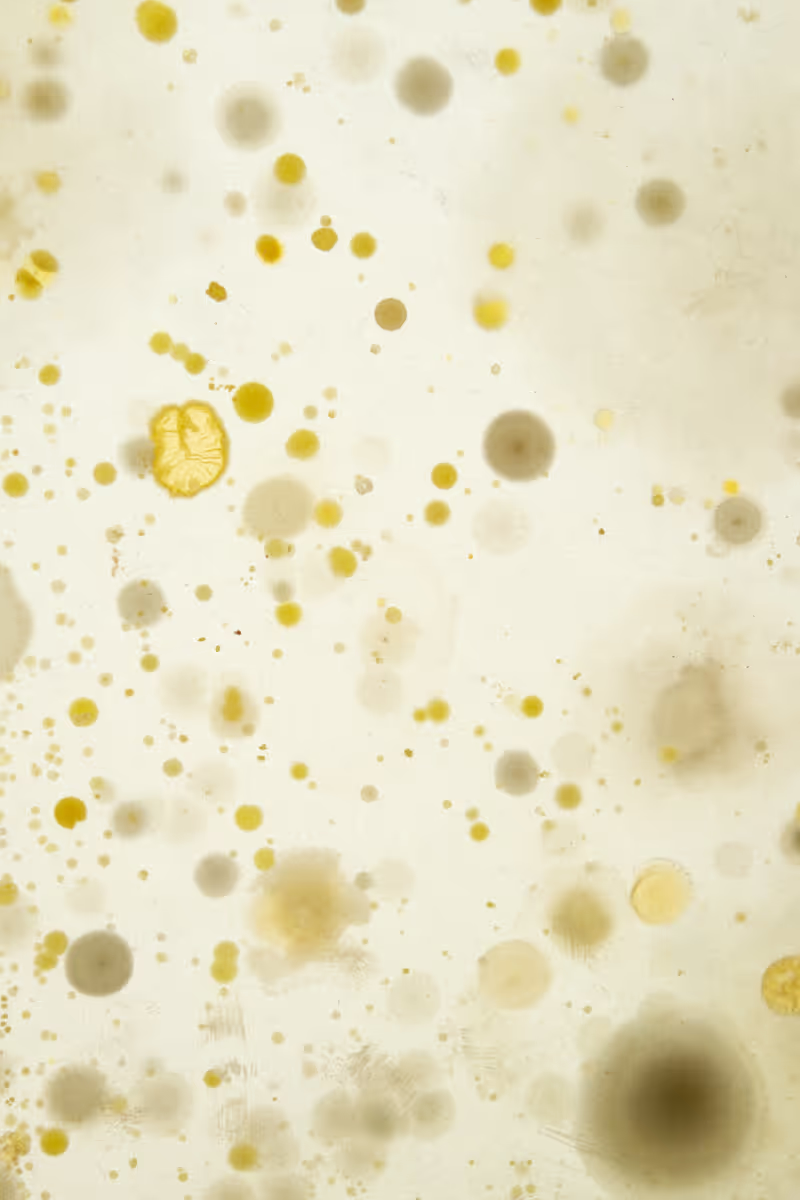

Юнак без рана не може - А brave fellow is bound to have wounds.

ЮНАК [juˈnʌk] is a word often used in Bulgarian folklore to describe a brave and intrepid youth.

The work depicts a series of “unnecessary memories” from the artist’s childhood. Reminiscences, not related to a significant event, unnecessarily stored in his mind. Ephemeral dreams of past moments. A futile gaze at a stranger’s face or a meaningless peer at a motionless object.

Юнак is part of Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2019.

recent stories

Events

futures activities

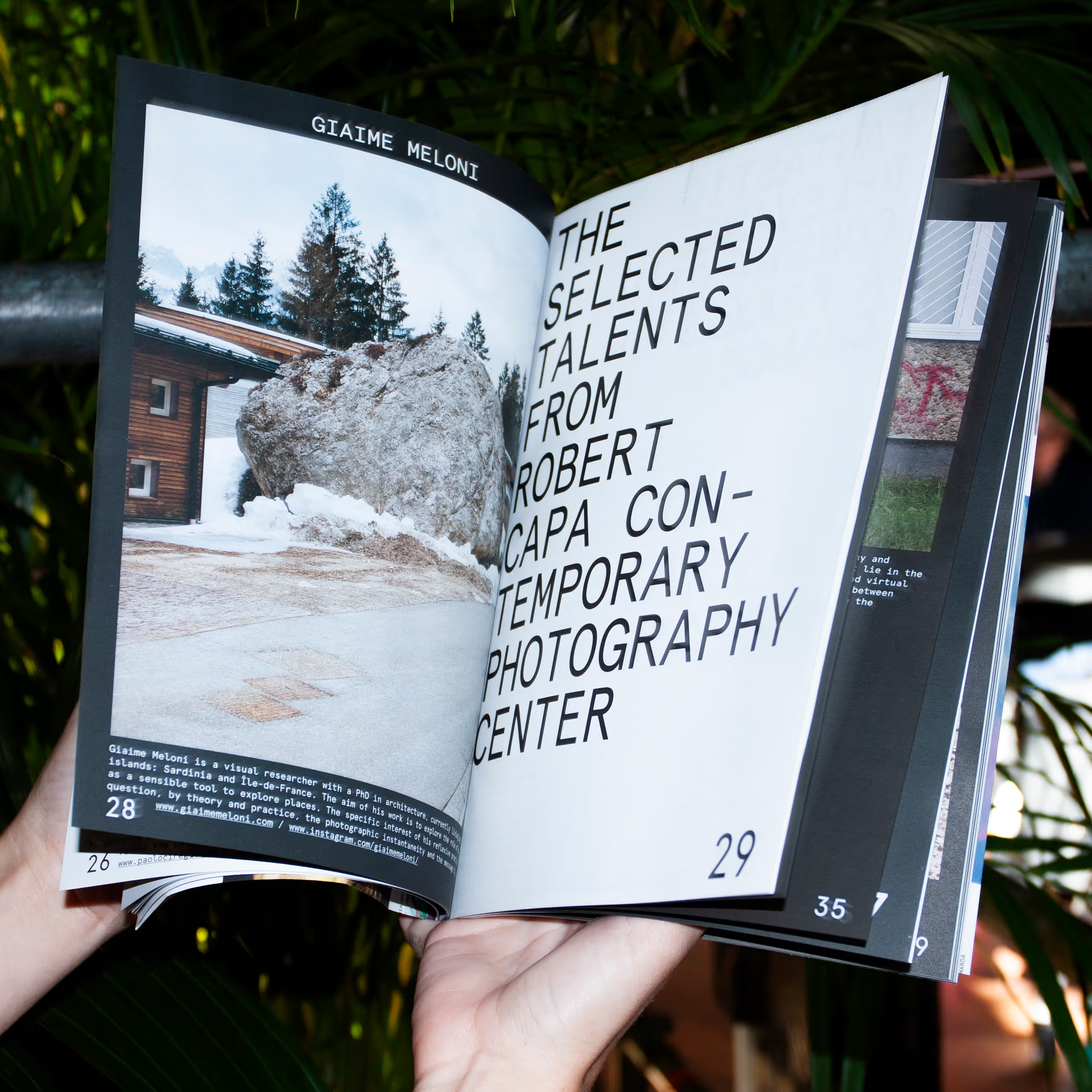

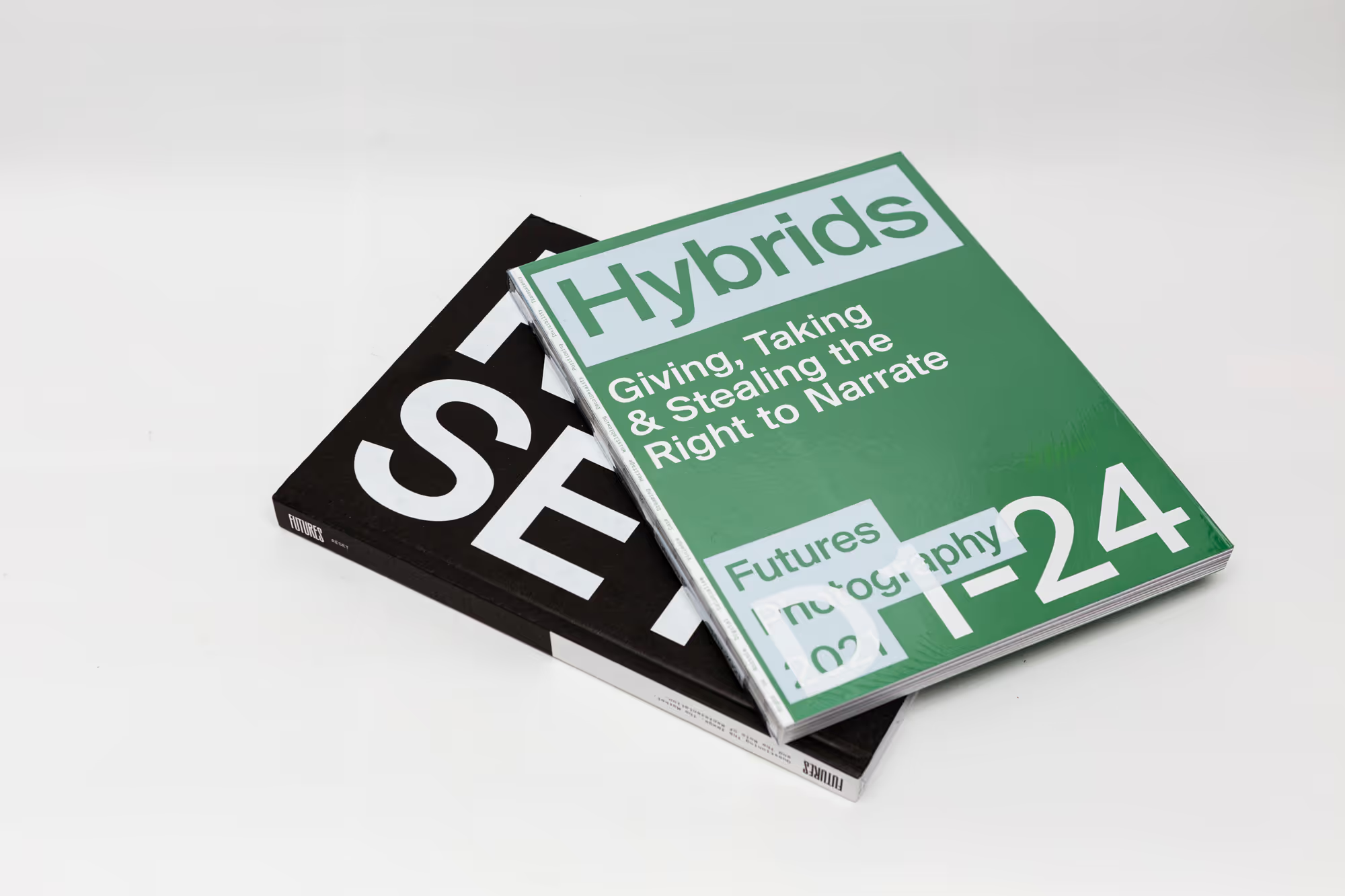

FUTURES is a European Photography Platform that brings together the global photography community to support and nurture the professional development of emerging artists worldwide.

FUTURES curates exhibitions and programs, including talks, through our extensive network of top European curators and artists.

The FUTURES Residency Program provides selected emerging photographers with the time, space, and resources to develop new work, with a strong focus on the artistic process and research.

FUTURES annual publications feature in-depth articles, interviews and conversations with key players from the global community. Released alongside the annual exhibition, the publication showcases work by FUTURES artists alongside commissioned essays on some of the most compelling issues in contemporary photography.