Although Yu Shuk Pui Bobby (31) speaks six languages, in her dreams, she often feels numb. “I want to scream,” she says. “I want to yell: Watch out! But nothing comes out. When it gets too scary, I wake myself up. I’ve learned how to do that – it’s like hitting a safety button.”

The dreams she has almost every night are always nightmares. When she wakes in the middle of the night, she records them on her phone. In the morning, she tries to make sense of what her subconscious is revealing – like navigating a vast, dark sea filled with hidden creatures.

“If you remember your dreams, it means there's something you need to uncover,” she says. “Once I understand what they’re about, healing can begin. And then,” says Yu Shuk Pui – who prefers to go by Bobby, “comes art.”

The nightmares are part of the process. Her whole life is part of the process. For Bobby to make her art – movies, videos, photographs, performances – she needs to understand what her mind is telling her. For the audience to grasp her work, they need to understand that her everyday life is just as essential as the research she conducts on her computer or in various archives.

“Artists are, first and foremost, humans. Art is human. My art is deeply connected to my personal life. So, when I wake up and write down my dreams – that’s important. I need to figure out what’s happening in my head before I can start creating. The same goes for tidying my room, drinking a cup of tea, or reading a book. If my personal life isn’t in order, I can’t do the work.”

Bobby has just arrived in Amsterdam from Oslo, where she lived for the past six years, studying at the Oslo National Academy of Fine Arts. She was born and raised in Hong Kong. Coming from a traditional and hierarchical society, she often draws from her upbringing and childhood experiences in her films, always revolving around a simple, three-letter question. Why?

Why weren’t her female cousins allowed to sit at the same dinner table as Bobby and her sister during a visit at their parent’s hometown? Why couldn’t she smoke like her male cousins did? Why didn’t her mother leave her father, despite her obvious unhappiness? Why is Bobby’s sexuality – an important part of her identity –so often ignored or silenced? And why is it that every question about the status quo is wrapped in taboos and superstitions that no one is allowed to challenge?

“For me, the most powerful thing was when I asked why?, people told me to shut up,” Bobby says. It only made her more determined. “People say I should just accept things and respect the way they are – but I don’t like that. Being curious, asking questions – that doesn’t mean that I’m attacking or disrespecting anything. It means I’m trying to understand.”

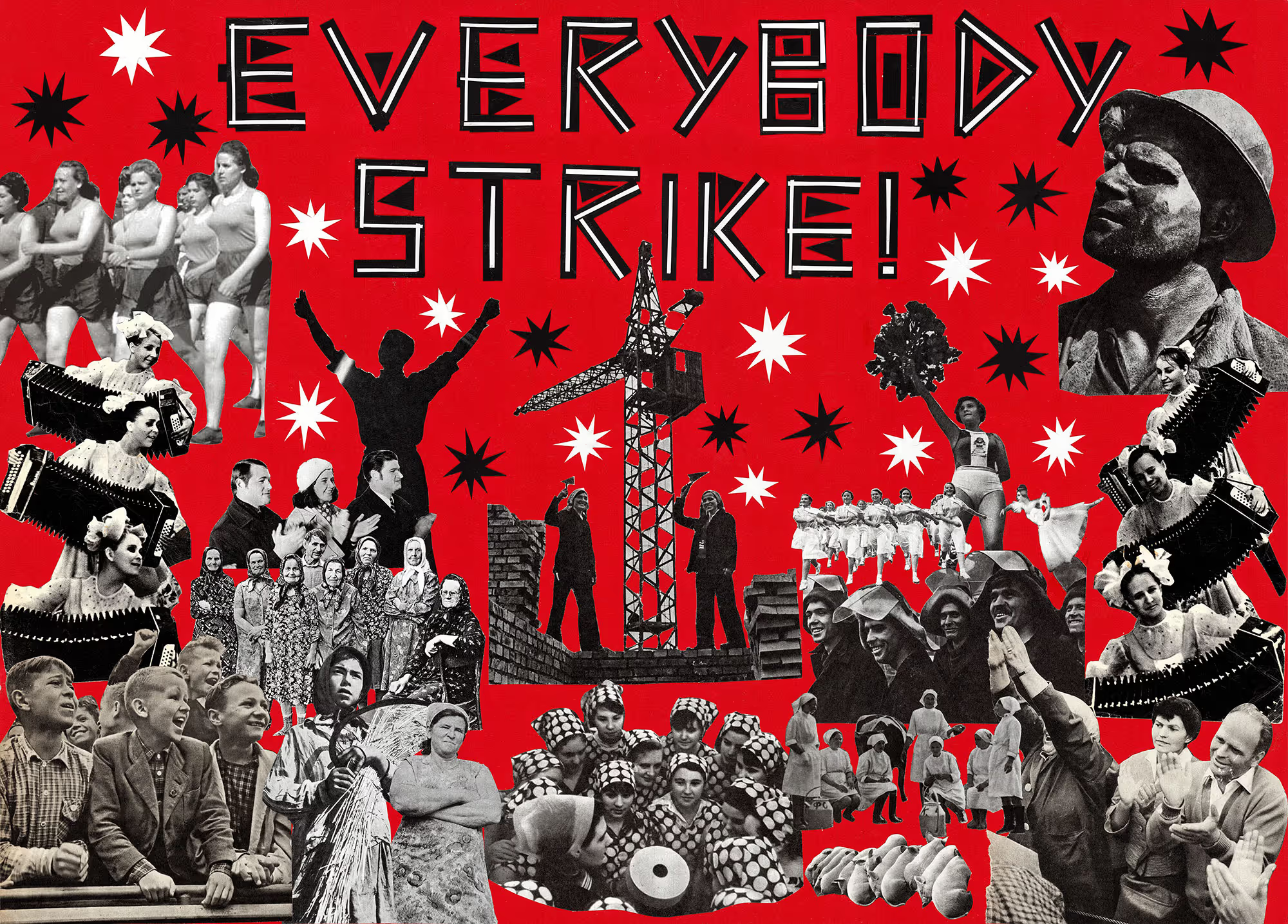

Her work connects her own personal traumas with broader, unspoken fears – those lingering just beneath the surface of society – any society, really, whether in Hong Kong or Norway or The Netherlands. This psychological dread often manifests as curses or ancient mythical creatures. In her work, they rise to the surface through pop culture references, like K-pop groups, anime, and horror films.

Take her newest project, Curses, Human-Faced Fish & Sadako Yamamura, which will be presented in November 2025 at Fotografiens Hus in Norway. It follows four young women training to become global pop stars – except three of them are secretly not human. One is a human-faced fish from Taiwan, another a huldra (a tailed forest spirit) from Norwegian folklore, and the third a green serpent from the Amazon. Don’t ask her how these characters ended up together – they just did. It’s what happens when dreams merge with waking life. It’s what happens when the subconscious is taken seriously.

“I always start from personal childhood and my own memory,” Bobby says. “But I’m also always searching for common ground with the audience.

For her recent film Whispers in the Belly, she hired a real therapist to lead two long sessions with her parents. “Under the flag of art”, they performed a script that she had written, but also played themselves – confronting real family issues and unspoken pain.

“It was terrifying, but ultimately a breakthrough. My parents don’t know much about art, but they went along with it – and they liked the film. I was able to reach them through my art. That’s what I want to keep doing: touching people, not just those inside the art world. I keep asking myself: What can art do – for me and for others? Not everything I make needs to be public. A lot of it can stay in the studio. But once I release something into the world, I need to think carefully about the how and the why.”

The residency at FUTURES in Amsterdam allows her to do research for new work – she has currently three ideas floating around in her head, waiting to surface. Later today she plans to stop by Chinatown for some much-needed dim sum, and then visit the Eye Film Museum.

“I want to watch some old European horror films, from the ‘70s or ‘80s,” she says brightly. “And learn more about the witch hunts.”

She also needs to clean. Make the space her own, even if only for two weeks. “That’s really important to me,” she says. “It takes time, but I don’t mind. I’m a slow-working artist anyway. I have to prioritise. In the end, art always shows up.”

It’s her seventh language.

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)

%2520Unseen-campaign-2024-square-forweb.jpeg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

%252C%25202015.jpeg)